These sketches describe the lives of our direct Webb, Alexandre, and Schenck ancestors, and are intended to inform additional research. These sketches are based primarily on existing family history and biographies, such as the 1969 biography James Watson Webb and the Journal of the American Revolution, but additional sources are cited as appropriate.

The early Webb family in America

In a privately-published 1881 biography of his father Samuel Blachley Webb’s famous Revolutionary war service, James Watson Webb described his family’s Colonial genealogy:

“Richard Webb was admitted a freeman of the town of Boston in April, 1632, and in the summer of 1635 emigrated to the banks of the Connecticut River in company with the Rev. Mr. Hooker and others, and settled in Hartford, where he was a land-holder in 1639. From there he removed to Stratford and subsequently to Stamford, where he died in 1676, leaving five sons and one daughter. His widow Elizabeth died at Norwalk in 1680. His son Joseph married Hannah Scofield in 1672, at Stamford, by whom he had one son (Joseph) and four daughters; and he died at Stamford in 1685. Joseph, the grandson of Richard, married Mary, the daughter of Benjamin Hoyt, in 1698, by whom he had five sons and three daughters. He died in 1743. His son Joseph, the great-grandson of Richard, married for his first wife Sarah Blachley, in 1726, by whom he had one son, Joseph, born at Stamford December 8, 1727. His wife Sarah died in 1733, and he married for his second wife, in 1736, Elizabeth Starr, by whom he had two sons, who were names Ezra and Ebenezer, and two daughters. His son Joseph, the great-great-grandson of Richard, the emigrant, removed to Wethersfield, Conn., with his half-brothers Ezra and Ebenezer, where Joseph married, in 1749, Mahetible Nott, by whom he had four sons – Joseph, Samuel B., afterwards General Webb; John, who died; and John 2d – and three daughters.”

Samuel Blachley Webb and Catherine Hogeboom

Samuel Blachley Webb (1753-1807) was the son of the Wethersfield, Connecticut merchant Joseph Webb, Sr. and Mehitable Nott (1732-1767), the daughter of a sea captain. Samuel is our fifth-great grandfather. He lived in a house his father built in 1749, which included a three-and-a-half story home and shop, with a large gambrel roof. The house and an associated house from the Deane family now are an active museum.

When Samuel was eight years old his father died, leaving behind a fortune, but also a complex business arrangement. Two years later, Mehitable Webb married the family attorney, Silas Deane. Deane turned out to be an exceptional mentor and father figure for Samuel. But, sadly, Samuel’s mother died when he was fourteen.

Samuel did not let his parents’ deaths deter him. By 1774 he established himself as the “chief factor” for a pair of trading ships financed by his older brother, Joseph Webb III, Silas Deane, and other Connecticut investors. He also assisted his step-father as he rose as a leader of the fight for Colonial rights. Deane served on the Committees of Correspondence and of Safety, and was elected to represent Connecticut at the First Continental Congress. Samuel was therefore a participant in the early independence movement. Samuel would meet with many of the leaders of the coming revolution, including George Washington, Benjamin Franklin, Robert Morris, and John Sullivan.

In the spring of 1775, Samuel was the ensign of the Wethersfield Militia Company and deployed to Boston. He and his company took a prominent role during the year-long Siege of Boston. According to Journal of the American Revolution author Phillip Giffin, the company provided guards for formal ceremonies such as prisoner-of-war exchanges, courts martial, hangings, and the general’s personal guards. They also fought in the June 1775 Battle of Bunker Hill, made famous in numerous articles at the time. Samuel was injured during the battle. Within a month of Bunker Hill, Webb was promoted to captain.

In the spring of 1776 General George Washington moved his men south from Boston to New York, and sought numerous aides de camp to manage the logistics. In June of 1776, Washington promoted Webb to the rank of lieutenant colonel and aide on his staff. Samuel worked for Washington during the difficult failed campaigns of 1776 and showed great resolve. Samuel was injured again at White Plains and Trenton. In January 1777, Samuel was promoted to colonel, and while leading a regiment at Long Island Sound he was captured by the British.

During his captivity, Samuel enjoyed a surprising amount of freedom of movement, and in the summer of 1779 he became engaged to Elizabeth Bancker of North Raritan, New Jersey. They married in secrecy on 22 October 1779, but Elizabeth died in childbirth in February 1781, according to researcher Jerry Gottsacker.

Samuel was released in a prisoner exchange in early 1781, and in May he joined a meeting with Washington and General Rochambeau at his childhood home to plan a final surge against the British, in which Samuel participated – ending in American victory.

Upon his retirement, he was promoted to Brigadier General by Washington. He remained a personal friend of Washington. He founded the Society of Cincinnatus and served as grand marshal at Washington’s inauguration in 1789. He also continued with the family’s shipping and mercantile businesses.

On 5 September 1790, Samuel married his second wife, Catherine Hogeboom daughter of Judge Stephen Hogeboom. They had nine children:

- Catharine Louisa Webb, 1792-1797.

- Maria Webb, 1793-1868; married George Morell.

- Henry Livingston Webb, 1795-1876; married Mary Ann Edmonds (1797-1874).

- Stephen Hogeboom Webb, 1796-1873

- Catherine Louisa Webb, 1798-1798

- Walter Wimple Webb, 1798-1876; married Julia Frances Converse (1807-1889).

- Rachel Webb, 1802-1869

- James Watson Webb, 1802-1884; married Helen Lispenard Stewart (1805-1848). James and Helen are our direct ancestors.

- Jane Hogeboom Webb, 1804-1875

- Sarah Lucy Webb, 1810-1877

- Jacob Lewis Webb, 1812-unknown.

Samuel and Catharine were buried at the Dutch Reform Church Cemetery in Claverack, New York.

James Watson Webb and Helen Lispenard Stewart

James Watson Webb (1802-1884) and Helen Lispenard Stewart (1805-1848) are our fourth-great grandparents. James was the orphaned son of the famous Revolutionary War General Samuel Webb and Catherine Hogeboom, and Helen was the daughter of prominent New York banker Alexander Stewart (1775-1838) and Sarah Lispenard (1783-1831).

James – always called Watson – got his start in the Army, looking for adventure. Despite a rule limiting commissions only to West Point graduates, he convinced Secretary of War John Calhoun to make him a lieutenant based on a moral debt owed to sons of Revolutionary soldiers. He would be called “Calhoun’s scrub lieutenant,” according to biographer James Crouthamel’s biography called James Watson Webb. He was first posted to Governor’s Island, New York, in 1819, and then to Fort Dearborn, Michigan, where he had occasional run-ins with American Indians.

By 1823, though, Watson was clearly thinking of a different future than the adventures offered by the American frontier. In July 1823, he married Helen Lispenard Stewart, and her good fortune. Watson and Helen would have the following children:

- Robert Stewart Webb, 1824-1899; married Mary VanHorne Clarkson. They had one son: Robert Stewart Webb, Jr.

- Lispenard Stewart Webb, 1825-1828.

- Helen Matilda Webb, 1827-1896; married N. Denison Morgan. They had one son, Robert Webb Morgan.

- Amelia Barclay Webb, 1829-1830.

- Catherine Louisa Webb, 1830-1918; married Capt. James Benton. The had two children: Mary Benton and James Benton.

- James Watson Webb, 1832-1832.

- Watson Webb, 1833-1876; married Mary Parsons. They had three children: Francis, Helen and Elizabeth Webb.

- Alexander Stewart Webb, 1835-1911; married Anna Elizabeth Remsen (1837-1912). Alexander and Anna are our direct ancestors.

Watson left the Army for New York in 1827. That same year, his father-in-law bought a newspaper – the Morning Courier – and installed James to run it. Two years later he purchased the Enquirer and merged the two as the Morning Courier and New York Enquirer. He then established a daily horse express between Washington and New York so he could get Washington news 24 hour before any other newspaper. All of this enabled him to develop a popular “political press,” taking a highly biased approach to reporting. He physically assaulted newspaper competitors on the street on more than one occasion – presumably in defense of his honor.

In his early political efforts, Watson was a supporter of Andrew Jackson ahead of the 1832 Presidential election, but later backed Henry Clay and coined the name “Whigs” for the new party that rose in opposition to Jackson’s presidency. In 1849 Webb was appointed Minister to Austria, but since he had backed Zachary Taylor over Clay for the Whig presidential nomination in 1848, Clay led Senate opposition, and Webb was not confirmed, according to researcher Bill McKern. In 1851 he was appointed Chief Engineer on the staff of New York’s Governor with the rank of Brigadier General.

After his wife Helen’s death in 1848, Watson married 22-year-old Laura Virginia “Lena” Cram (1826-1890), the daughter of a wealthy brewer, and they had five sons:

- William Seward Webb, 1851-1926; married Eliza Osgood Vanderbilt (1860-1936) in 1881. Watson named William Seward Webb after New York Governor William Seward. After fighting a duel with Thomas F. Marshall, a member of congress from Kentucky, Watson was convicted in 1842 and served two months of his sentence but was pardoned by the Governor. Shortly after his marriage into the Vanderbilt family, William took over management of the Wagner Palace Car Company, which later merged with the Pullman Company. Webb also became President of the Adirondack and St. Lawrence Railroad, the Mohawk and Malone Railway and other ventures. He developed Shelburne Farms.

- George Creighton Webb, 1854-unknown.

- Henry Walter Webb, 1856-1919; married Amelia Howard (Griswold) Codman (1856-1910). “H. Walter” took part in the Orton expedition that traced the Amazon River nearly to its source. He joined his brother William as an executive of the Wagner Palace Car Company, and became an executive with the New York Central Railroad. He was also a Director of the National City Bank and more than twenty other companies and banks.

- Jacob Louis Webb, 1857-1928

- Francis Edgerton Webb, 1859-unknown.

Watson was a friend and supporter of Abraham Lincoln – a Republican. He and his wife Laura attended Lincoln’s inaugural. At the start of the Civil War in 1861, he declined both a commission as a Brigadier General in the Army and appointment as Minister to Turkey. He accepted the post of Minister to Brazil, a position in which he served until 1869. As Minister, Watson negotiated an agreement with his longtime acquaintance, French Emperor Napoleon III, that led to French withdrawal from Mexico and the reestablishment of Mexico’s sovereign government, also according to Bill McKern.

Watson and Helen first lived with her father at 151 Hudson Street, but moved to suit the needs of their growing family – to Broad Street in 1830, to 96 Greenwich Street in 1832, and then to 6 Carroll Place. But the place that the family would really call home was an estate called Pokahoe on the Hudson River near Tarrytown, according to the James Watson Webb biography. Watson’s second wife Laura would move into the Pokahoe estate and they raised their five sons there, as well, until they sold it 1862.

As Watson and Laura grew older, they traveled extensively, including a three-year tour of Europe. Later they would pass the time with games of whist and billiards, reading novels and attending Episcopalian services. But Watson was frequently troubled by gout, and it would contribute to his physical demise. James Watson Webb died on 7 June 1884 and was buried at Woodlawn Cemetery in the Bronx, New York, along with Laura, who died on 16 January 1890. Their grave is marked with a massive monument and plaque – perhaps appropriate for a man once called “the last of the Barons.”

Alexander Stewart Webb and Anna Elizabeth Remsen

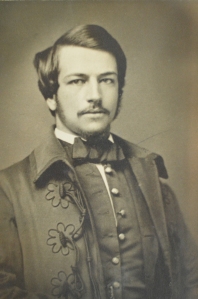

Alexander Stewart Webb (1835-1911) and Anna Elizabeth Remsen (1837-1912) are our fourth-great grandparents. Alexander, called “Andy” by his father (according to an interview with his third-great grandson, who knew Alexander’s daughters), was born on 15 February 1835 in New York City.

Alexander attended West Point Military Academy and graduated 13th in his class in 1855, along with future generals on both sides of the impending Civil War. He focused on mathematics while a student, but also enjoyed sketching – a skill that would prove very useful during his military career. He studied under the Hudson River School artist Robert Walter Weir, and socialized with the artist James Whistler, who was thrown out of the 1855 class for mocking a chemistry teacher in a sketch. Alexander’s third-great grandson has the fading Whistler sketch.

Alexander married Anna Elizabeth Remsen (1837-1912), daughter of Hendrick “Henry” Rutgers Remsen (1809-1874) and Elizabeth W. Phoenix (1807-1890), on 28 November 1855, about the time of his graduation from West Point. Anna was further descended from Henry Rutgers Remsen, Sr. (1762-1843), an early financier and bank executive in New York City, who also served as private secretary to Thomas Jefferson during Jefferson’s time as Secretary of State under George Washington, according to her 16 November 1912 New York Tribune obituary and the Henry Remsen papers in the New York Public Library.

Henry Rutgers Remsen, Sr., did an extraordinary job of documenting Anna’s family’s history in detail. In one 9-page record he titled “Family Register: Henry R. Remsen’s book,” he described his own marriage and children, and when Henry Rutgers Remsen died, his son continued to enter information. In another book called “Family Record of Henry R. Remsen and Elizabeth W. Phoenix 1834,” Hendrick “Henry” Rutgers Remsen provides 47 pages of births, marriages, vaccinations, accidents, deaths and more. Both records offer incredible depth of description of the family and surrounding events, and are offered here for posterity.

Alexander and Anna would have eight children:

- Henry Remsen Webb, 1857-1858.

- Helen Lispenard Webb, 1859-1929; married John Ernest Alexandre (1830-1910). Helen and John are our direct ancestors.

- Elizabeth Remsen Webb, 1861-1926; married George Burrington Parsons (1863-1939) in 1891.

- Anne Remsen Webb, 1868-1943; unmarried.

- Alexander Stewart Webb, Jr., 1870-1940; married Florence L. Sands (1872-1941). Became the president of the Lincoln Trust Company in 1908.

- Caroline LeRoy Webb, 1868-1950; unmarried.

- William Remsen Webb, 1872-1899. Commissioned as an Army Lieutenant; died at Huntsville, Alabama in the service of the 16th US Infantry.

- Louise DePeyster Webb, 1874-1910; married John Wadsworth.

Shortly after his graduation from West Point, Alexander was sent to Florida to participate in the Third Seminole War. After his service in Florida, Alexander returned to West Point to teach math.

With the outbreak of the Civil War in 1861, Alexander Webb launched a heroic wartime career, participating in many of the war’s worst fights. A terse biography offers some highlights:

“At the beginning of the war, he took part in the defense of Fort Pickens, was present at First Manassas, was assistant to General William F. Barry, Chief of Artillery for the Army of the Potomac from July 1861 to April 1862, and during the Peninsula Campaign was Barry’s acting inspector general. He was Chief of Staff for General Fitz-John Porter’s V Corps during the Maryland Campaign in 1862.

“In January 1863 he became Assistant Inspector General of the V Corps and a few days prior to the Battle of Gettysburg took command of the famous Philadelphia Brigade of the II Corps, being promoted to Brigadier General, US Volunteers on the same day (June 23rd). During Pickett’s Charge on July 3rd his four regiments were posted at the Clump of Trees at the Union center, the focal point of the Confederate attack. He lost 451 men killed and wounded during the assault. He was wounded as well.

“He was again wounded, this time severely, at the Battle of Spotsylvania in May 1864 and did not return back to duty until January 1865. At this time he assumed the duties of Chief of Staff for Gen. George G. Meade, a position he held until the end of the war. He was breveted Major General, US Volunteers in both the regular and volunteer armies at the end of the war, and appointed Lieutenant Colonel of the 44th United States Regular Infantry.”

That Alexander made it out of the war alive is astonishing. At Gettysburg, he was seen in the open, leaning on his sword and puffing on a cigar, during a terrifying artillery bombardment (the brunt of the brutal Pickett’s Charge.) He was shot through the leg during the ensuing close combat, and after the battle sent a telegram (now in the possession of the Huxley family) to his wife saying, “Am well. Not wounded. Only scratched.” During the Battle of Spotsylvania the next year, a bullet entered his right eye socket and exited by his ear, leaving a crease from his eye socket to his ear. He was always photographed after from the other side. He rejoined the fight later in the year. For his “distinguished personal gallantry” at Gettysburg, he was awarded the Medal of Honor in 1891.

In an existing letter, Anna was urged by Julia Grant, the wife of General Ulysses S. Grant, to get as close as possible to the fight. From photographs in the Huxley family’s possession it appears that Anna took Julia’s advice by making trips to the rear of the Union force to accompany her husband.

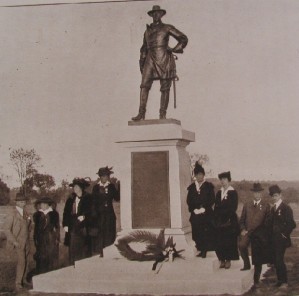

Alexander returned to great acclaim in New York after the war, and remained at West Point as a professor of mathematics until 1870. He served as the second president of the City College of New York until 1902, where he attempted to maintain a classical curriculum. He also served as the first president of the Westminster Kennel Club. In 1881 he wrote the book, The Peninsula: McClellan’s Campaign of 1862. General Alexander Webb is honored with statues at Gettysburg and at the City College of New York, and is the subject of an installment at the Gettysburg museum.

General Webb’s statue near the Angle at Gettysburg. He selected this spot for placement.

Dedication Day, the Family of General Alexander Webb at the monument,October, 12th, 1915.The monument was unveiled by Miss Anne R. Alexandre, Granddaughter of General Webb. (http://gettysburgsculptures.com/gen_webb_monument)

Alexander and Anna lived out their days in a large house overlooking the Hudson River in the Riverdale suburb of New York City, just south of Westchester County. Their grandchildren adored them, and lovingly called them Cuckoo and Grandmoo. They were buried together at Section M, Site 22, of the West Point cemetery.

John Ernest Alexandre and Helen Lispenard Webb

John Ernest Alexandre (1830-1910) was the son of Francis Alexandre and Marie Civilise Cibrian, according to his death certificate. His father was a Catholic born on the Isle of Jersey. John was born in New York City. The family’s New York City home was located at 35 East 67th Street and had a stable at 173 East 73rd Street. The Alexandre’s Long Island estate was called Valley Brook Farm.

John inherited ownership of the Alexandre Steamship Line, which sailed between the U.S. and Brazil in the mid 1800s. Later, the line was called the New York, Havana & Mexican Mail Line, and provided the first regularly scheduled steamship service between New York and Veracruz, eventually expanding to other Mexican ports and Cuba, according to shipping historians. The Ward Line bought the Alexandre Line in 1888. Family history maintains that the Alexandres got their start in shipping as privateers.

![[New York, Havana & Mexican Mail Line (Alexandre Line)]](https://i0.wp.com/www.crwflags.com/fotw/images/u/us~nymex.gif)

He married Helen Lispenard Webb (1859-1929) on 11 May 1887. Together, they had the following children:

- Helen Lispenard Alexandre, 1889-1953; married Bayard Cushing Hoppin (1884-1956) by her father’s deathbed at his insistence. Bayard was the grandson of a Rhode Island governor.

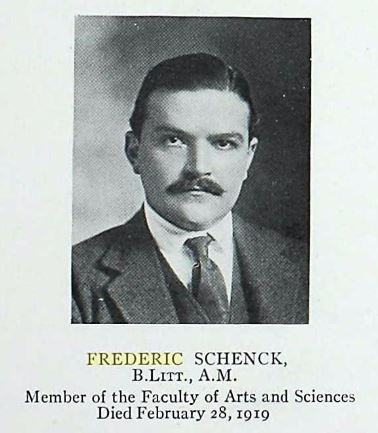

- Marie Civilise Alexandre, 1891-1967; married the Harvard professor Frederic Schenck (1886-1919) on 30 June 1917. Marie and Frederic are our direct ancestors.

- Anna Remsen Alexandre, 1895-1984.

John and Helen built a summer house called Spring Lawn on Kemble Street in the Berkshires in 1903, according to a history of Berkshire cottages. Helen and their daughters had been coming to Lenox for a decade and were renting the Frelinghuysen house next door when Spring Lawn was built by Boston architect Guy Lowell.

John died an early death from bladder cancer in 1910, surrounded by family in their Berkshire home. The family continued to live in Manhattan and the Berkshires, until Helen’s death in 1929.

Frederic Schenck and Marie Civilise Alexandre

Frederic Schenck (1886-1919) and Marie Civilise Alexandre “Civi” (1891-1967) are our second-great grandparents. Frederic was born on 10 October 1887 at Lawrence, Long Island, and after finishing his preparation at the Groton School he entered Harvard University in 1905. In 1909 he received the degree of A.B. cum laude, with distinction in History and Literature of the Middle Ages, according to a Harvard Crimson memoriam. He then spent two years in Oxford University, earning the degree of Litt.B. in 1912. He received the degree of Ph.D at Harvard in 1918.

In the summer of 1912, Frederic competed as a fencer in the Olympics in Stockholm, making it to the quarterfinals in individual épée. These were the same games that Jim Thorpe, Duke Kahanamoku, and George Patton competed in. Frederic lived in Paris that summer and applied for a passport to travel in Russia. His application indicates he stood 6’3″ and was mustachioed, with brown hair and brown eyes. He traveled for a year in Germany, France, Russia, Poland and Belgium, describing the sights in great detail in a pair of thick journals.

Frederic’s Schenck ancestors originally settled in America in the 1630’s,according to the Brooklyn Museum, which features two Schenck farmhouses in their entirety, along with the family Bible. Freddy and Civi Schenck lived at Valley Head, which burned in 1987, according to local historians. Our father remembers sitting on the porch of Valley Head while his grandmother (Civi “Granny Schenck”) told him her memories of watching the soldiers return from the Civil War in Madison, Indiana from her family home (the Lanier Mansion, on the Ohio River, now owned by the state of Indiana.) Later, Frederic would live with his wife on historic Brattle Street in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

The Harvard Graduates’ Magazine and the Washington Herald reported on Frederic and Civi’s 30 June 1917 wedding, with the Herald writing:

“Mrs. Charles R. Shepard, of Washington, will be among the guests at the marriage today of Mr. Frederic Schenck and Miss Marie Civilise Alexandre in Lenox. Others among the guests there for the wedding are: Mr. and Mrs. Cushing Hoppin, brother-in-law and sister of Miss Alexandre, who are with Mrs. John E. Alexandre, her mother; Mr. and Mrs. David M. Osborn, of New York, who are with Mr. and Mrs. Hamilton Fish Benjamin, and Mrs. Charles S. Guthrie, of New York. who is with Mrs. J. Frederick Schenck, who is to entertain Prof. and Mrs. Harold Edgell and Prof. and Mrs. Roger B. Merriman, of Cambridge. Mass. Mrs. Shepard is also the guest of Mrs. Schenck.”

Frederic and Marie had one child:

- Anne Remsen Schenck (Nancy), 1918-1993; married David Bruce Huxley (1915-1992) in 1939. Anne and David are our direct ancestors.

Frederic was a member of the Harvard faculty, an instructor and tutor in the Division of History, Government, and Economics, chairman of the Committee on Degrees with Distinction in History and Literature, and secretary of the Committee on the use of English. He’s credited by the University of Pennsylvania for translating at least two significant books, including Giotto and Some of His Followers and Comedies by Holberg: Jeppe of the Hill, The Political Tinker, Erasmus Montanus.

Marie Civilise (Alexandre) Schenck was listed on the 1919 Boston Social Register, and all seemed fine. But that same year her husband’s life was cut short by pneumonia, leaving her alone with their infant daughter. Freddy almost certainly was victim to the same extraordinarily deadly influenza pandemic that killed 50-100 million others globally in 1918-1920. Civi would never remarry, and 48 years later would be buried beside her husband near her family’s summer home in the Berkshires.

Professor R.B. Merriman provided strong praise for Frederic in the Harvard Crimson:

“Names, dates, and official titles, however essential for historic record, are likely to convey but an inadequate idea of a man’s real life and work. In the present case they are even less significant than usual. The key to the characters and career of the man whom Harvard mourns today was his overflowing. human sympathy. It enabled him to vitalize everything to which he set his hand, to turn the most perfunctory and mechanical bit of drudgery into an interesting and important task. It was the source of his success as a teacher and administrator. It made him a host of friends, young and old, who flocked to him for help and advice on every conceivable subject.”

David Bruce Huxley and Anne Remsen Schenck

David Bruce Huxley, Q.C. (1915-1992) and Anne Remsen Schenck (1918-1993) were our great grandparents. David was born to Leonard Huxley and Rosalind Bruce in London, 21 years after his half-brother Aldous Huxley was born. David loved his older half-siblings, but his much later birth meant some social separation from them. He was naturally closer to his younger brother Andrew, the Nobel Prize winner.

David was educated at Christ Church College at Oxford, and was proud of being the youngest Queen’s Counsel at the time. He also said he was the only QC to have spent a night in jail (for pinching a policeman’s helmet) He was at the Inns of Court when war broke out, then he joined the Court Regiment and thrived in his military service. He began as a Second Lieutenant in the Royal Tank Regiment and went to North Africa, where he fought Rommel in the desert. According to his son, David “got blown to hell”, developed vascular dysentery, and was sent to a hospital in Cairo.

At the end of his convalescence he was reassigned to Iraq for 3-4 years, where he put together a small defense force. He loved doing the spying, according to his son, but knew they’d fall apart if the Germans arrived. He played desert polo and hunted for foxes in his down time, and established a house of leisure for the troops. David left the Army as a Major.

After his return from the war, David gained appointed posts in Bermuda as the solicitor general, attorney general and acting chief justice of the Supreme Court – for a total of almost two decades. He made Bermuda attractive to US investors. He compiled and revised the “Private and Public Acts of the Legislature of Bermuda 1620-1953,” a seven-volume work. The 1953 West Indies and Caribbean Yearbook lists David as the Attorney General.

David married Anne Remsen Schenck (1918-1993) in the Spring of 1939 in Chelsea. Anne was the daughter of Frederic Schenck (1886-1919) and Marie Civilise Alexandre (1891-1967).

Anne also took part in the war effort, possibly serving in the OSS in the early war according to family history, and then as a London ambulance driver and social aid organizer. She wrote her mother frequently during the war, describing constant Nazi air raids and the damage it inflicted on the community. She recounted being thrown by an explosion and injuring her nose. But she took most of it in stride, commenting in one letter that “war becomes me.”

David and Anne had the following children:

- Angela (Huxley) Darwin. Angela married George Pember Darwin in 1964. The marriage of a Huxley to a Darwin – a natural selection – attracted some media attention.

- Frederica Huxley of London

- Virginia Huxley of Columbia, Missouri

- Elizabeth Huxley of St. Louis, Missouri

- Michael Huxley of Albany, New York; married Carole Corcoran.

Under pressure from his wife to move to New York, David took a position as a vice president and legal adviser to Arnold Bernhard and Company and the Value Line Fund in New York from 1957 to 1976. He and Anne lived at 251 East 71st Street. But the marriage did not survive the transition to New York and they divorced in 1961.

After his divorce from Anne, he married Ouida Branch Wagner (1918-1998) in 1964. They retired to England in the late 1970s, where David took on the duties of warden of his local church. He loved the “bells and smells” of the church, according to his son.

David died of heart failure on 6 September 1992 at their home in Wansford, England, according to a New York Times obituary.